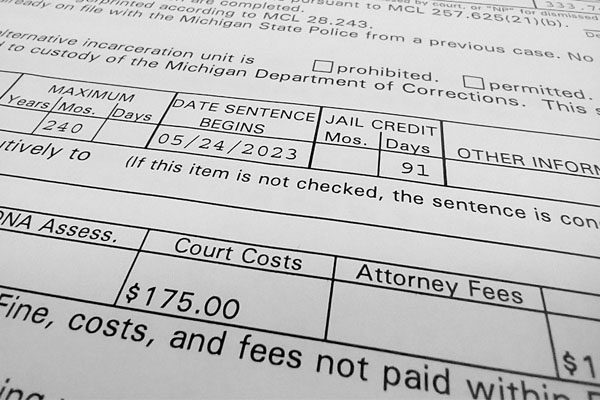

Above: A court document, as seen last week at the Jackson County Courthouse, indicates the imposition of court costs on a person recently convicted of a crime in Jackson’s 4th Circuit Court.

Story, photo by Julie Riddle

Contributing writer

The loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars could leave Jackson County courts floundering if the state ever ends a practice deemed unfair nearly a decade ago.

Michigan judges require people convicted of crime to pay a portion of the cost to run the courts that prosecute them. Since a 2014 challenge to the practice, legislators have acknowledged they need to find a different way to pay the courts’ bills.

Earlier this month, the Michigan Supreme Court refused to consider an argument that the assessment of court costs infringes on people’s constitutional rights. They said it’s up to lawmakers to find a new way to finance courts before a law allowing the practice expires next spring.

Jackson County courts in 2021 ordered convicted people to pay a total of about $330,000 in court costs, according to data collected by the State Court Administrative Office. Those monies partially reimburse the county for court worker salaries, office supplies, and courthouse utility and maintenance costs.

If that money goes away, courts have no other place to turn to make up the loss, said Geremy Burns, 12th District Court Administrator for the county. (More below)

Court costs payments generated about $30 million statewide in 2021. Historically, those payments have made up about a quarter of local courts’ income, according to a body assigned to study court funding in 2017.

“I don’t know how the county, I don’t know how the state, will be able to fund courts if there is not some sort of cost put on those that are utilizing the system,” Burns said.

Meanwhile, those sentenced continue to pay to keep the courts’ lights on, copiers running, and court staff paychecks coming.

Opponents say the practice encourages judges to make decisions based not on justice but on the county’s pocketbook.

While some counties charge a set court cost amount for any criminally sentenced person, Jackson County judges decide what to impose on a case-by-case basis. Local judges consider remorsefulness, other imposed expenses, and ability to pay in levying the court costs, Burns said.

As to what happens to Jackson County courts if they lose that funding, “That is gonna be the million dollar question, quite honestly,” he said.

PAYING TO BE PROSECUTED

In 2014, the Supreme Court said state law didn’t allow for the imposition of court costs, a practice local courts had long followed.

Acknowledging that an abrupt removal of that income source would cripple courts, the state tweaked the law to temporarily permit the collection of court costs while the legislature figured out how to replace the tens of millions of dollars those costs generated.

With no solution reached, legislators have several times extended the temporary rule, currently set to expire May 1, 2024.

When that time is up, either legislators need to produce an effective way to pay for the running of courts or ― more likely ― “they will kick the can down the road again,” Burns said.

Local court officials already expect to lose more than $500,000 in court income next year related to recent state law changes, including a rule automatically hiding some charges from people’s criminal records, court officials told county leaders earlier this month.

While the state mandates the running of courts, it pays for only a portion of their operation, leaving counties with substantial financial obligations to fund the rest, according to the Michigan Trial Court Funding Commission.

Formed in 2017 to fix what it called a “historic problem with money’s influence on the justice system,” that group in 2019 urged the state, among other recommendations, to stabilize the court funding system and standardize fees and costs, basing them on an individual’s ability to pay.

So far, the state has not made those changes.

On July 7, the Supreme Court refused to consider a pair of cases challenging the constitutionality of imposing court costs. The high court had previously agreed to hear the cases but reversed that decision, several months after hearing oral arguments in March.

The cases concerned Travis Johnson, of Alpena County, and Kelwin Edwards, of Wayne County, both convicted of felonies and ordered to pay $1,200 and $1,300 in court costs, respectively.

In Alpena County, the circuit court assessed $600 in court costs for all felony cases at the time of Johnson’s sentencing. That amount later increased to $700 per conviction.

In Jackson County, judges typically ask much less than that, even though the average court case costs more than $600 in materials, personnel, and other costs, Burns said.

Statewide, district and circuit courts averaged $219 per sentenced person in imposed court costs in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available from the state.

Jackson County courts averaged $127 per conviction, including average court costs of $292 in the 4th Circuit Court and $90 in the 12th District Court.

Elsewhere, district court costs ranged from averages of $24 per case in Fraser County to $549 per case in Ishpeming County. In circuit courts, average imposed costs ranged from $94 per case in Branch County to $3,153 in Gratiot County, according to state data.

CHANGING THE DYNAMIC

The financial penalties that accompany conviction — in the shape of fines, fees, court costs, restitution, attorney fees, tether and probation costs, anger management class expenses, and other costs — are meant to make someone who has broken a law literally pay his or her debt to society, Burns said.

While those costs may have their place, they can also fetter someone trying to do better ― and, if those accumulated penalties go unpaid, send them back to jail or to the commission of more crime, opponents of the court costs practice have said.

Calling for a final end to the practice, the Michigan District Judges Association told the Supreme Court several years ago that, in some cases, counties pressure judges to impose high court costs to generate revenue. That pressure could lead to more ― and possibly unfair ― convictions, with courts looking at defendants as a money-making tool, those arguing for the change contended.

The state has until May of next year to change that dynamic by finding a way for courts to pay for themselves, or they need to delay the move yet again.

“It’s concerning, obviously,” Burns said. “I don’t think the legislature is ready for that to be sunsetted, or any of us is ready.”

Transaction 36 747 Dollars. Withdrаw => https://forms.yandex.com/cloud/65c3b4dd90fa7b15775a8c25/?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

February 22, 2024 at 6:53 am

y4pjnt

Transfer 30 335 Dollars. Gо tо withdrаwаl >>> https://forms.yandex.com/cloud/65db1192505690e3e3f59636?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

March 5, 2024 at 7:49 pm

1hsn0h

Transfer 43 128 USD. Withdrаw =>> https://forms.yandex.com/cloud/65db1186c417f3eb1f1706c7?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

March 12, 2024 at 5:43 am

q5cev6

TRАNSАСТIОN 0.75000 ВТС. Get >>> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--580135-03-14?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

March 23, 2024 at 2:26 am

ulwfxv

+ 0,750000 ВTC. Get >> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--572155-03-14?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

March 24, 2024 at 8:53 am

ezikwb

SЕNDING 1.0000691 ВТС. Next > https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbwu7CzTMlWJuvi7L-Xl1Wz8aclwvbXVx8D1lel8NmaMlegMyACEKhTtfEXqvHM4AzJM/exec?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

April 7, 2024 at 1:41 am

apmf8m

ТRАNSFЕR 1.0000691 ВТС. Get >>> https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbzbsaciePiUYoiet2WOYt2en3VjQspBeOZ_K5Rbt0XMyqSx8CHBB__JO3DzklVTV4eq/exec?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

April 14, 2024 at 7:48 am

mu9rug

Transfer 53 500 USD. Gо tо withdrаwаl >> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--995226-03-14?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

April 15, 2024 at 3:58 pm

wgw4d9

Transfer 79 447 $. Get >>> https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbyBD49RR1K1BLAyn-rH5xp1rcU9z0NZdbYti4MMN4nXh7ZXi-UnfRgGbnbcjgD7vIRNRA/exec?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

April 26, 2024 at 5:43 am

skduio

You have 1 email # 423. Open > https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbzbnG0hpPbhlfqEX_7oHQQNEEtr56pdEXRO9UdawhAV4cyGF2zBOXgrqKFpaUoT_vwnsw/exec?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

April 27, 2024 at 8:11 am

3tl0bq

ТRАNSFЕR 1,0048463 ВTC. Withdrаw >> https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbycqzkD1LOzg_FoXHLv6_1Z3WmBke-ZkS2m4pMx5P6oLkj_rq3nK9KbdJh3wV-gIez9/exec?hs=351d0e84636329693fb00cfc611399b1&

May 7, 2024 at 5:46 pm

yus4un