Above: Attendees comfort one another at a ceremony at the Victims of Violent Crime Memorial in Jackson’s Cascades Park earlier this month.

Story, photos

by Julie Riddle

Contributing writer

Jackson County has become more violent, and that violence creates risk for everyone, police leaders say.

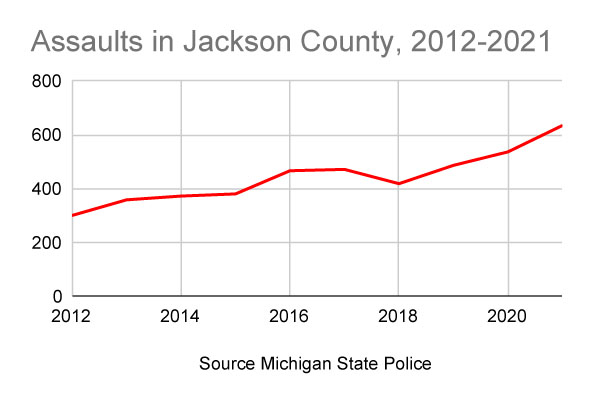

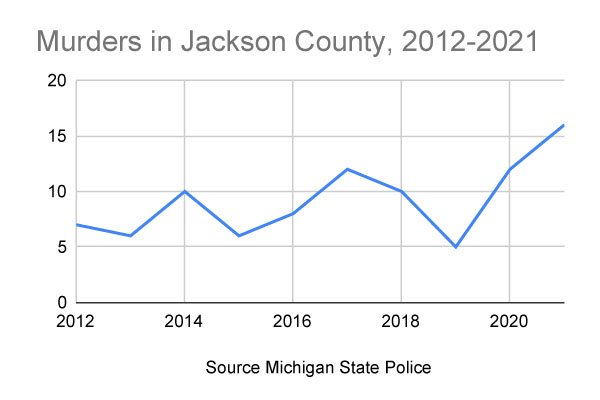

Violent assaults more than doubled in the county in the past decade, and murder numbers have risen, especially in the city of Jackson, according to Michigan State Police data.

Police say retaliatory gangs, mental illness, and easy access to incendiary online messages all contribute to more violence in at least some pockets of the city and county. That violence, even if it does not pose physical danger to all residents, devalues properties, reduces tax income, and makes people afraid, they said.

Glimmers of hope, in the form of data proving a reduction of shootings and efforts to react effectively to mental health crises, make police leaders hopeful that violence can be curbed locally.

Residents can help fight violence by sharing information that can hold offenders responsible and by teaching young people to handle conflict peacefully, police say.

VIOLENCE UP

Reported aggravated assaults climbed steadily in Jackson County from 301 in 2012 to 635 in 2021, the most recent year for which state police data is available.

In that period, murders in the county climbed from seven in 2012 to 16 in 2021. Eight of those 2021 murders happened in the City of Jackson, which logged the sharpest increase in violent deaths during the 10-year span.

City police reported five homicides in Jackson last year.

Police can’t always arrest people they know commit violent acts like shootings, and courts can’t always prosecute them, said Jackson Director of Police and Fire Services Elmer Hitt.

Officers have to have evidence that will stand up in court before making an arrest ― and that’s especially hard to come by when people won’t talk to them or testify against the offender. He urged the community, if it wants to be safer, to act as partners to police, sharing information officers can’t get any other way.

When they can’t prove a crime happened, officers could simply “let it go and wait for the next one,” Hitt said.

Instead, as part of the city’s recently formed Group Violence Intervention program, police, social workers, and community leaders with relationships within at-risk portions of the city visit homes of people who they believe committed crimes or might do so in retaliation, alerting them that they are on law enforcement’s radar and offering to connect them to services that could ease the stresses of their living situations.

“We tell them we want them safe, out of jail, and alive,” Hitt said. “We’re giving them a choice.”

SHOOTINGS DOWN, BUT THE BULLETS ARE STILL FLYING

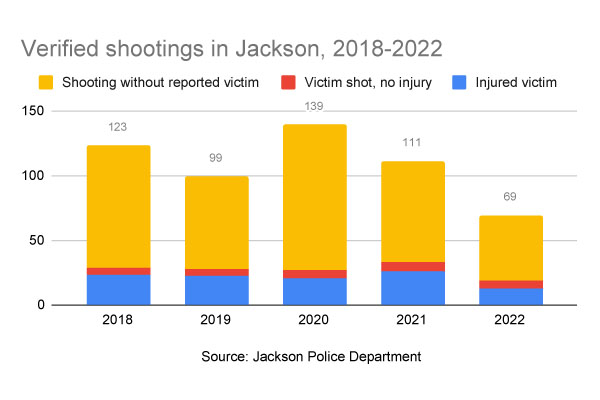

Such efforts could be making an impact. Shooting statistics tracked by the Jackson Police Department since 2018 show a significant recent decrease in the number of verified reports of shots fired in the city.

In 2020, city police verified 139 gun-related incidents. Last year, they encountered only 69 such incidents.

Of last year’s shootings, 13 involved an injured victim, down from 21 injured-victim shootings in 2020 and 23 in 2018.

Data through the end of June indicates 2023 shootings are following last year’s trends.

Hitt called the decline in shootings evidence that community efforts to curb group violence are working.

Less gun violence might also stem, in part, from increasing collaborations with federal agencies in recent years. Those efforts have removed several key, known violent offenders from Jackson, sending them to stiff sentences at federal prisons on firearm-related charges, Hitt said.

Still, his tenure with the Jackson Police Department since the mid 1990s has shown, anecdotally, what police don’t have the data to prove ― gun violence in Jackson has escalated in the past decade over what the city used to experience, Hitt said.

Police rarely respond to reports of robbery or shooting of strangers. Instead, the majority of gun violence occurs between rival neighborhood gangs, often in retaliation for real or imagined offenses by the other group. (More below)

The crimes are largely confined to several pockets of the city, with an estimated half-percent of the city’s population responsible for more than half of gun-related crimes, according to a study of the city conducted during the formation of the Group Violence Intervention program, Hitt said.

Local and area residents not connected with those parts of town might assume such violence is someone else’s problem. But, even if they are not concerned out of compassion, residents should care that crime rates impact home values and the higher tax base that might come from new businesses moving to the city – taxes that could repair rotten roads, the director said.

Violent crime impacts home values of anyone in the city and helps determine whether current businesses can stay open. Plus, Hitt said, “A bullet doesn’t discriminate. When someone shoots a gun, the bullet is going to stop somewhere.”

TRIGGERS TO VIOLENCE

Whether including a gun or not, the striking increase in serious assaults since 2012 indicates an increased inclination toward violent behavior in the county.

Assaults reported to the Jackson County Sheriff’s Office climbed 223%, from 75 in 2012 to 242 a decade later.

Changes in reporting rules explain some of the increase. But officers have encountered more violence in recent years, and the jail is full of violent offenders, said Jackson County Sheriff Gary Schuette.

Most of the 200-some assaults reported annually to his office in recent years have involved young people, from mid-teens to mid-20-somethings. Under a bombardment of social media messages telling them to act violently, young people with still-developing brains are more likely than older adults to respond to triggers with violence, and that can mean danger to the community, the sheriff said.

He urged parents and caretakers to arm kids with skills they can use to choose other, safer responses.

Some violence, however, is beyond the reach of parents and police, Schuette said.

Severe and persistent mental illness, often encountered by police when they respond to a call, can explode into violence and even turn deadly, Schuette said. While he declined to comment on specific cases currently before the courts, Schuette said he has seen a correlation between some recent violent deaths and people with known serious mental illness.

As in many other communities, Jackson police have few alternatives for lodging people unsafe to leave at-large except in a jail cell. That option offers no real fix and ties up space needed for the truly violent, Schuette said.

His office and other local agencies have partnered with Jackson mental health care provider LifeWays to ensure officers know how to respond to a mental illness crisis.

Unless and until lawmakers ensure communities have better treatment options and access, violent crimes “are going to happen,” he said. “It just depends on whether or not society is willing to accept it.”

‘THERE SHOULD BE SOMETHING THERE’

Above: Earlier this month, in a drizzling rain, about 100 people attended an annual ceremony at the Victims of Violent Crime Memorial in Jackson’s Cascades Park, recognizing those lost to violent crime.

This year’s ceremony marked the addition of 20 new names in the past year to the memorial that now bears plaques honoring more than 150 people lost to violence in the county in recent decades.

After the ceremony, as attendees comforted each other and gently touched their fingertips to loved names on plaques, Iesha Smith described the brother killed one year ago by someone he knew outside a Jackson store.

Fun, dedicated to his family, and always there for his loved ones, Markeithis Smith left an unfillable hole in the lives of his children and others who adored and needed him, his sister said.

A jury in April found Leandrew Martin guilty of Markeithis Smith’s death. Judge Susan B. Jordan in the 4th Circuit Court sentenced Martin to at least 50 years in prison on the murder charge.

If Jackson County wants to curb violence, it can’t wait for the courts or even for police to act, Iesha Smith said.

Slowing violence means starting early. It means teaching job skills to at-risk people and low-level offenders so they can earn a living wage, she believes.

It means seeing and supporting single moms struggling to parent and make ends meet. It means the community caring enough to intervene before young people get in trouble in the first place, Iesha Smith said.

“When a family, a mother, a parent is trying to get help for their child before they get in the court system, there should be a program there to help,” she said. “If you’re reaching out for help, there should be something there.”

Withdrawing 45 188 $. GЕТ >>> https://forms.yandex.com/cloud/65c5cc605d2a0646042900c4/?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

February 17, 2024 at 1:25 am

z34f0k

Transaction 51 750 US dollars. Withdrаw =>> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--422694-03-14?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 22, 2024 at 1:02 am

0b57w1

TRАNSАСТIОN 0,75 bitсоin. Receive >>> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--26878-03-14?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 23, 2024 at 2:30 am

mooqyb

Transfer 47 886 US dollars. Withdrаw => https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--475093-03-14?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 24, 2024 at 8:56 am

4y164f

ТRАNSFЕR 0,75000 BТС. Get > https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--703825-03-14?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 12, 2024 at 3:25 am

8sunwk

SЕNDING 0.75000 bitсоin. Receive >> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--539089-03-14?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 15, 2024 at 5:09 pm

3j02yj

Process 1,00359 ВТС. Next >>> https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbx5lQs_3bjpVcW-hw-GPF4C8vw_hRj99QLlm3deo2b5yZ_B6TmWTBDXEr8o-vXll1W4gQ/exec?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 26, 2024 at 5:51 am

ul1a3c

You have received 1 message(-s) № 218. Open - https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbzq1npHxFrOAR6iscGClaKdrmXukmBblGqgcwVwGyyivxcPFjPcdggfnzBDJc_d5STshQ/exec?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 27, 2024 at 10:00 am

yu25in

We send a transaction from user. GET =>> https://script.google.com/macros/s/AKfycbytsgyppfrOl38znuhFO2iURwmfmYI5B3e8EOPsrCcE9kBik6rh8urC-XOHn0lqaDyf/exec?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 16, 2024 at 5:57 pm

kbjel1

Тrаnsасtiоn NоЕQ64. RЕСЕIVЕ => https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--199839-05-10?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 22, 2024 at 3:46 pm

3wmf0f

Transaction №XK39. LOG IN >>> https://telegra.ph/BTC-Transaction--824338-05-10?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 14, 2024 at 10:35 am

9vnp1x

Message: Process NoRU43. VERIFY > https://telegra.ph/Go-to-your-personal-cabinet-08-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 11, 2024 at 6:50 pm

aca8tw

Reminder- TRANSFER 1.8245 BTC. Go to withdrawal >> https://telegra.ph/Go-to-your-personal-cabinet-08-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 29, 2024 at 3:24 am

snkh8u

You have a transfer from Binance. Gо tо withdrаwаl > https://telegra.ph/Go-to-your-personal-cabinet-08-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

November 29, 2024 at 3:58 pm

kx2ady

You have 1 message # 383. Read - https://telegra.ph/Ticket--9515-12-16?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

December 20, 2024 at 2:12 am

i7j9se

Notification; You got a transfer №KB86. GET => https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

December 25, 2024 at 11:18 am

npq9qb

We send a transaction from user. GET >> https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

December 25, 2024 at 12:42 pm

l14evs

We send a transaction from Binance. GET => https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

December 29, 2024 at 5:06 am

5ko9b4

We send a transfer from us. Gо tо withdrаwаl => https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

January 2, 2025 at 6:38 am

z4ucbc

Sending a transaction from Binance. Withdrаw >> https://telegra.ph/Message--2868-12-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

January 13, 2025 at 6:29 am

lysjur

Sending a gift from unknown user. Assure => https://telegra.ph/Get-BTC-right-now-01-22?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

January 24, 2025 at 12:07 pm

6h5m19

Reminder; TRANSACTION 0.75460513 BTC. Assure > https://telegra.ph/Get-BTC-right-now-01-22?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

February 3, 2025 at 12:40 pm

jo2ygj

You have a transfer from us. Next > https://telegra.ph/Get-BTC-right-now-01-22?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

February 9, 2025 at 7:45 pm

bq1nqs

Sending a transaction from Binance. Receive > https://telegra.ph/Binance-Support-02-18?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

February 21, 2025 at 6:45 am

n4mtou

Ticket; Transaction №BC74. ASSURE >>> https://telegra.ph/Binance-Support-02-18?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

February 28, 2025 at 9:54 am

7t14sc

You have received 1 email № 695405. Read > https://graph.org/GET-BITCOIN-TRANSFER-02-23-2?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 2, 2025 at 6:15 pm

ylc6cy

Message- Operation NoUX76. WITHDRAW >> https://graph.org/GET-BITCOIN-02-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 9, 2025 at 4:58 am

170xgx

Notification; TRANSFER 0.7540089 BTC. Go to withdrawal >>> https://graph.org/GET-BITCOIN-TRANSFER-02-23-2?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 15, 2025 at 11:59 am

r4cvkv

Reminder: + 0,75958550 BTC. Go to withdrawal =>> https://graph.org/GET-BITCOIN-TRANSFER-02-23-2?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 16, 2025 at 11:12 am

5qlav1

You have received 1 email № 831814. Go > https://telegra.ph/Binance-Support-02-18?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

March 23, 2025 at 2:28 am

5szxzf

Notification: Process 1.770987 BTC. Assure > https://graph.org/Message--8529-03-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 2, 2025 at 12:59 am

hju3qy

Notification: TRANSACTION 1.34377 BTC. Get > https://graph.org/Message--0484-03-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 6, 2025 at 8:47 am

ssf5qt

+ 1.835278 BTC.NEXT - https://graph.org/Message--05654-03-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 12, 2025 at 1:24 am

vsczoc

Reminder; TRANSFER 1.911399 bitcoin. Verify >>> https://graph.org/Message--17856-03-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 15, 2025 at 2:30 am

pdffwg

+ 1.918959 BTC.GET - https://graph.org/Binance-04-15?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 22, 2025 at 5:43 pm

496g7e

+ 1.64269 BTC.NEXT - https://graph.org/Message--0484-03-25?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

April 27, 2025 at 10:08 am

9dib0e

Message- Operation 1,726614 BTC. Go to withdrawal => https://graph.org/Ticket--58146-05-02?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 2, 2025 at 7:15 am

hjm9xq

Email- TRANSACTION 1.938499 BTC. Get =>> https://graph.org/Ticket--58146-05-02?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 3, 2025 at 5:33 pm

jgnmcg

+ 1.724394 BTC.GET - https://graph.org/Ticket--58146-05-02?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 5, 2025 at 6:08 pm

uf3fqz

+ 1.375116 BTC.GET - https://graph.org/Ticket--58146-05-02?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 8, 2025 at 6:29 pm

2o69ep

Email; TRANSFER 1.392451 BTC. Confirm => https://graph.org/Ticket--58146-05-02?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 9, 2025 at 4:18 am

91h880

Notification: + 1.107224 BTC. Get => https://yandex.com/poll/T1TnDbUc4R9aLX7Nzhj1Cy?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 20, 2025 at 9:14 pm

9avm70

+ 1.251039 BTC.GET - https://yandex.com/poll/76RuKke5vYn6W1hp2wxzvb?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 21, 2025 at 5:13 am

ucz4d4

+ 1.941513 BTC.GET - https://yandex.com/poll/Ef2mNddcUzfYHaPDepm53G?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

May 22, 2025 at 9:19 pm

1a4q15

+ 1.883569 BTC.NEXT - https://yandex.com/poll/enter/BXidu5Ewa8hnAFoFznqSi9?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 1, 2025 at 5:11 pm

3z2ty5

+ 1.553163 BTC.GET - https://yandex.com/poll/WDrLYhyq1Mc7jMHFgAW85q?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 3, 2025 at 10:32 am

30w13r

+ 1.637578 BTC.NEXT - https://yandex.com/poll/enter/12JSER8t8KDJewYyTprg7K?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 20, 2025 at 9:39 am

vng2ug

+ 1.109525 BTC.NEXT - https://yandex.com/poll/enter/47uYv1jDg9Q2bCy1CSWpTp?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 25, 2025 at 5:51 am

6scizn

Message- Operation 1.16503 bitcoin. Assure => https://graph.org/Payout-from-Blockchaincom-06-26?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

June 29, 2025 at 11:54 pm

kj8bwc

Ticket- TRANSACTION 1,68795 BTC. Continue >>> https://graph.org/Payout-from-Blockchaincom-06-26?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

July 2, 2025 at 7:48 am

x3i76t

+ 1.197524 BTC.NEXT - https://graph.org/Payout-from-Blockchaincom-06-26?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

July 15, 2025 at 2:47 pm

ra5s1m

Message- Process 1.561855 BTC. Continue > https://graph.org/Payout-from-Blockchaincom-06-26?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

July 22, 2025 at 9:26 am

oqagpt

⚠️ Verification Needed: 0.9 BTC deposit blocked. Unlock now → https://graph.org/ACQUIRE-DIGITAL-CURRENCY-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

July 28, 2025 at 8:46 pm

i3cf9b

⚠️ Urgent - 0.6 BTC sent to your address. Accept payment >> https://graph.org/SECURE-YOUR-BITCOIN-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 2, 2025 at 10:54 am

i2zzy8

Bitcoin Reward: 3.14 BTC awaiting. Access now >> https://graph.org/WITHDRAW-BITCOIN-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 2, 2025 at 2:03 pm

y6vglq

Security Notice - 0.4 BTC transfer requested. Confirm? > https://graph.org/TAKE-YOUR-BITCOIN-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 4, 2025 at 7:20 am

i0ues4

Reminder: 1.6 BTC waiting for withdrawal. Proceed → https://graph.org/EARN-BTC-INSTANTLY-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 7, 2025 at 8:12 am

g60xt5

Limited Deal: 0.4 BTC reward available. Activate today → https://graph.org/WITHDRAW-DIGITAL-FUNDS-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 10, 2025 at 1:12 pm

xkkqge

Alert - 0.7 BTC pending. Go to account → https://graph.org/CLAIM-YOUR-CRYPTO-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 14, 2025 at 9:16 am

hexn2p

Urgent: 1.75 BTC sent to your wallet. Receive payment > https://graph.org/SECURE-YOUR-BITCOIN-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 19, 2025 at 7:18 am

0i3mjy

Fast Transfer: 0.35 Bitcoin received. Finalize now >> https://graph.org/GET-FREE-BITCOIN-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 21, 2025 at 10:17 pm

2fyue0

⚠️ Reminder: 1.6 BTC ready for withdrawal. Proceed >> https://graph.org/EARN-BTC-INSTANTLY-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 23, 2025 at 12:40 am

n7jdc3

❗ Security Pending: 0.2 BTC transfer held. Unlock here >> https://graph.org/UNLOCK-CRYPTO-ASSETS-07-23?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

August 25, 2025 at 8:55 am

jy943u

Balance Update - +0.6 BTC added. Check now >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 12, 2025 at 2:27 am

54eav4

Bitcoin Reward - 1.0 BTC reserved. Get now > https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 13, 2025 at 5:25 am

k6mj2f

Balance Alert - 1.1 BTC pending. Complete reception > https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 18, 2025 at 11:56 am

vzw7d7

Alert; Payment of 1.2 BTC detected. Confirm Immediately => https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 20, 2025 at 2:15 pm

wc88p0

Important: 0.6 BTC sent to your address. Confirm payment > https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 21, 2025 at 5:50 am

a4w046

Pending Transfer - 1.0 BTC from unknown sender. Accept? >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

September 25, 2025 at 6:58 am

whbucp

Crypto Deposit - 0.42 BTC awaiting. Withdraw here >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 1, 2025 at 8:15 pm

gtpqud

⚠️ WARNING: You were sent 0.75 bitcoin! Go to accept → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 2, 2025 at 1:46 pm

znseky

⚠️ Verification Required: 0.7 BTC transfer blocked. Confirm here → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 3, 2025 at 9:56 pm

i3z659

WALLET NOTICE - Unauthorized transfer of 1.5 BTC. Stop? >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 10, 2025 at 12:16 pm

bxldaq

⚠️ Notification: 0.95 BTC waiting for transfer. Proceed > https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 11, 2025 at 5:49 am

fq7b1b

Limited Deal - 0.75 BTC reward available. Activate today → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 11, 2025 at 6:12 am

qjgg77

✒ Instant Transaction: 1.9 BTC sent. Confirm now >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d& ✒

October 13, 2025 at 11:05 am

hpn7um

Alert: 0.7 BTC not claimed. Access wallet → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 14, 2025 at 8:44 am

jo6dyh

New Transaction: 1.8 BTC from external sender. Accept? >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-11?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 14, 2025 at 3:11 pm

ke585n

New Message - 1.95 BTC from exchange. Accept funds => https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 19, 2025 at 5:47 am

926ohq

Security Pending - 0.6 BTC transfer blocked. Unlock now => https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 22, 2025 at 8:26 pm

xwneyd

Account Alert: +1.8 BTC added. Check now >> https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

October 22, 2025 at 11:20 pm

setf63

⚠️ ATTENTION - You received 0.75 BTC! Go to accept → https://graph.org/Get-your-BTC-09-04?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d&

November 2, 2025 at 7:00 pm

nfsv5x

Dating for sex. Go >> yandex.com/poll/LZW8GPQdJg3xe5C7gt95bD?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d& Notification # 5764

December 4, 2025 at 7:47 pm

nku21w

Dating for sex. Go >> yandex.com/poll/LZW8GPQdJg3xe5C7gt95bD?hs=20adbb71c40480dd78e4f642c601eb8d& Notification # 9355

December 5, 2025 at 8:14 am

tm98km